In 1896 a woman shot dead a Liverpool merchant who she believed had broken a promise to marry her. She was sentenced to death but was reprieved due to her mental state and spent 55 years in Broadmoor.

In the early 1890s, whenever Edgar Holland went to London on business, he enjoyed liaisons with Catherine Kempshall, a Sussex born theatre chorus girl. When Holland decided to end the affair, she was furious and sued him for breach of promise in 1895, claiming that he had reneged on a marriage proposal.

The dispute was settled out of court by counsel, but Kempshall was unhappy with this as in return for a financial settlement, Holland wanted all letters returned. She successfully applied to the High Court for this agreement to be set aside. In July that year Kempshall represented herself but the judge ruled against her, saying that there had been no promise of marriage.

Kempshall then undertook a year long campaign of harassment against Holland. Taking up lodgings at 40 Irvine Street in Edge Hill she bombarded him with letters. She would often turn up unannounced at his office in Water Street and and home in Penkett Street, Wallasey, where she told his housekeeper that she would shoot him.

In an attempt to keep Kempshall at bay, Holland occasionally gave her sums of money and wrote saying he was willing to offer a settlement but only if she instructed a solicitor. However she responded by saying that there was no need for her to do so as law was a "thieving profession".

Eventually a meeting was set up between the two at Holland's office at Drury Buildings in Water Street, facilitated by his solicitor Mr Alsop. Holland again told her that although he had no moral or legal obligation, he was prepared to provide for Kempshall but only via a solicitor. She again refused, saying that they were all liars and rogues. Then she took a revolver from under her coat and fired it four times at Holland, the bullets hitting him in the chest, thigh and hand. Alsop bravely ran around the table and pinioned her, causing the firearm to fall from her hand. A policeman was sent for and Kempshall was found to also have a dagger in her possession.

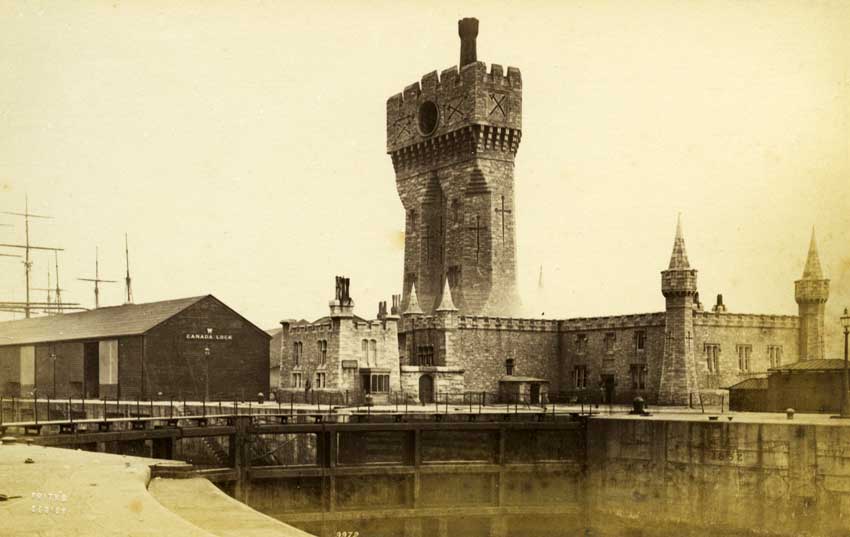

Holland was taken to the Northern Hospital, where surgeons removed a bullet that had penetrated his lung. He was so weak that he was unable to make a deposition and his condition remained critical. Kempshall was taken to the Bridewell where she was charged with attempted murder. A search of her lodgings found further ammunition in a small box.

Two weeks later, Holland from a collapsed lung. This cause of death was attributed solely to the bullet wound and he was generally considered to be in good health otherwise. This led to Kempshall being committed to the assizes on the charge of murder.

There was a huge crowd outside St Georges Hall on 19th March the following year as crowds sought admission to Kempshall's trial. She appeared in the dock dressed in all black and wearing a hat and veil. Although appearing weak and distressed, she replied in a firm voice "I am not guilty" when asked to enter her plea. She then undertook an extraordinary tirade in which she insisted the gun had gone off accidentally and called Alsop a liar, before saying she hoped none of the jury were Holland's friends. She had to be told firmly to "shut up" by her counsel.

In opening the case for the prosecution, Mr Pickford said that there was no doubt that Kempshall has shot Holland, with the only thing under question being her state of mind at the time. Alsop was the first witness and he recounted the day of the shooting as well as confirming that a bundle of letters produced, all signed by Kempshall, had all been sent to his office. An employee of Holland said that Kempshall had gone to Drury Buildings on fifteen occasions when he was away on business in Switzerland.

Two doctors testified that Holland's death was solely as a result of the shooting. When challenged on why they didn't operate on the collapsed lung, they replied that he was in too weak a condition and would have died from shock or exhaustion. Maud Park, who had rented a room out to Kempshall at Irvine Street, said that it had been taken under the name of Lock and that she said a solicitor owed her money. Holland's housekeeper was unable to testify due to ill health, and evidence was then heard that Kempshall had spent fourteen days in gaol for slapping the solicitor who represented him in the civil proceedings.

For the defence, the first witness was solicitor William Quilliam who had seen Kempshall in her cell soon after her arrest. He described how she didn't appreciate why she was there, was unable to give coherent sentences and would constantly throw herself back in her seat. Dr Wigglesworth, of the Rainhill Asylum, stated that although Kempshall as sane on other topics when it came to that of Holland, she was suffering delusions that all solicitors and judges were conspiring against her. This, he said, had influenced her conduct as it made her of unstable and excitable temperament.

Dr Beamish, the Medical Officer of Walton Gaol said that Kempshall had been very weak on arrival and immediately taken to the hospital wing. He was of the opinion that she was suffering from mania persecution as she could discuss other topics calmly but would become excitable at the mention of Holland's name. Another surgeon, Dr Davies, told the court he believed that Kempshall was insane "where Mr Holland was concerned".

In the closing speech, Kempshall's counsel Mr Madden said that her demeanour in court and words used in the letters showed that her mind was in a disordered state, something that medical professionals had confirmed. She then interrupted however, saying "I am not a maniac, I am quite sane, it is the truth what I say". Drawing his speech to a close he urged the jury to spare her life as "she knew not what she did".

In his summing up, which lasted half an hour, the judge said that suffering from delusions did not make somebody criminally irresponsible. He told the jury to consider the nature of the delusion and crucially, did it make Kempshall believe that she had to shoot Holland because he was armed himself and about to kill her. At 7pm the jury retired to consider their verdict and after ninety minutes returned to court having found her guilty of murder, but with a strong recommendation of mercy.

Asked if she had anything to say before sentence was passed, Kempshall gave a long speech in a calm and composed manner. She said she had been misled by her solicitors, that Alsop was a liar and that the gun went off accidentally as Holland rushed and tried to dislodge it from her when he saw she had it. There were gasps in court as she said she did not want a reprieve. When sentence of death was passed Kempshall said "He will" in respect of the Lord having mercy on her soul. She was taken to the condemned cell at Walton Gaol where she developed a resigned acceptance to her fate.

A petition was raised by Mr Quilliam at his offices in Manchester Street. Support came from surprising quarters, with Alsop and also Holland's brother Walter both calling for the death sentence to be commuted. A total of 17,796 signatures were gathered and on 31st March a reprieve was granted. This was on the basis of a review of Kempshall's mental state, which concluded that she be removed to the Broadmoor Asylum. Reports stated that Kempshall showed no emotion as she was told of the decision.

Catherine was taken to Broadmoor by train from Woodside on 1st April. She was never released from the institution, dying there in 1952 at the age of 88.

Shevlin demanded the money back and Varley gave it to him, saying they should meet up outside. Varley went out of the Great Charlotte Street exit but Shevlin, keen to avoid confrontation, left by the door that led to Deane Street. Sensing this, Varley went round to Deane Street and struck Shevlin, who didn't respond and ran off towards Ranelagh Street. Varley gave chase and struck Shevlin again opposite Lewis's, but this time Shevlin fought back. He was seen by an excited crowd to take something small and shiny out of his pocket and hold it out to Varley, who fell down bleeding.

Shevlin demanded the money back and Varley gave it to him, saying they should meet up outside. Varley went out of the Great Charlotte Street exit but Shevlin, keen to avoid confrontation, left by the door that led to Deane Street. Sensing this, Varley went round to Deane Street and struck Shevlin, who didn't respond and ran off towards Ranelagh Street. Varley gave chase and struck Shevlin again opposite Lewis's, but this time Shevlin fought back. He was seen by an excited crowd to take something small and shiny out of his pocket and hold it out to Varley, who fell down bleeding.