On the evening of Saturday 31st January 1885 Mary Calvert went to a market with her four year old daughter, returning to her home in a court off Watkinson Street at 11pm. Her 28 year old husband James was immediately argumentative demanding to know where they had been. When she replied that they had been to markets he reacted angrily, kicking her in the abdomen.

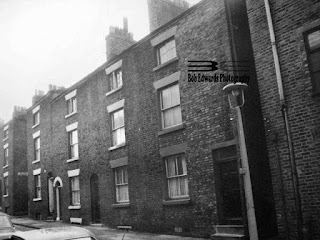

On the evening of Saturday 31st January 1885 Mary Calvert went to a market with her four year old daughter, returning to her home in a court off Watkinson Street at 11pm. Her 28 year old husband James was immediately argumentative demanding to know where they had been. When she replied that they had been to markets he reacted angrily, kicking her in the abdomen.Mary ran into the street crying for help but her husband ran after her and kicked her repeatedly in the lower part of the body, causing her to lose consciousness. After going inside for a short period, Calvert only realised the seriousness of what had happened and returned to the street after pleas from neighbours. One of them shouted to him 'were your hands not enough' and he said to her 'it has got nothing to do with you stop interfering.'

25 year old Mary was taken to the Southern Hospital in a cab but she died about fifteen minutes after being admitted, never having regained consciousness. A post mortem found that she was pregnant and the cause of death was determined as uterine haemorrhage and Calvert was arrested, then remanded for a week pending the outcome of an inquest. After a verdict of wilful murder was found he was committed to the assizes which were just about to begin.

Calvert was then on trial with his life at stake as soon as 11th February, the case being heard by the formidable Mr Justice Day, known for his harsh sentences. Neighbours gave evidence as to what they had seen and a surgeon from the hospital said that Mary had been in robust health and her injuries could not have been caused by a fall. In defence, Calvert tried to say he had not kicker her and she had fallen over a stool, then said his wife had been drunk for seven weeks and he was angry that he had been out at work and no dinner was ready for him. He pointed out that he took her to hospital and also remained with her until she died.

In summing up Justice Day said the jury had to determine if Calvert really did intend to cause grievous bodily harm. Without leaving their box they returned a verdict of manslaughter but there was no leniency when it came to sentencing, with the judge ordering that he serve twenty years in prison.